Inheriting money can be both emotional and overwhelming. In this blog, Retirement Planners Loren Merkle and Clint Huntrods explain how different types of assets—cash, investments, retirement accounts, real estate, life insurance, and personal property—are treated, which tax rules to watch for, and how to make thoughtful decisions that fit into your bigger retirement plan.

When a loved one dies, and you receive an inheritance, grief and logistics collide. As Loren put it, “in most cases you need to take a little bit of time before you make decisions on those investments.” That space to breathe matters—yet some items can be time-sensitive, so knowing what you’re dealing with is step one.

Below, we break down common inherited assets, key tax considerations, and strategies—using examples from Loren and Clint.

1. Cash and Taxable Accounts

Often the simplest. Cash you receive generally isn’t taxable at the moment you receive it; any interest that accrues after the date of death can be taxable to you. Timing can still be tricky if the estate holds cash back until probate wraps up.

Clint has seen firsthand how deadlines can add stress to an already difficult time. “We actually just saw an example with a family we just started working with where she inherited an account from her dad’s workplace and they gave her a 90-day window to get those assets transferred out,” he said.

Clint added that in the midst of grieving, she also had to make time-sensitive and emotionally complex decisions.

2. Individual Stocks and Mutual Funds

When you inherit investments like stocks or mutual funds outside of an IRA or 401(k), you generally benefit from what’s called a step-up in cost basis.

Here’s what that means: the “cost basis” is essentially the starting value the IRS uses to calculate your taxable gain when you sell. Instead of inheriting your loved one’s original purchase price, the cost basis “steps up” to the Fair Market Value on the date of death.

Example: Grandma bought XYZ stock years ago at $100/share. At the time of her death, the stock was worth $300/share. When you inherit it, your new cost basis is $300/share. That $200/share of growth during Grandma’s lifetime is wiped out for tax purposes—you won’t owe taxes on it.

If you later sell the stock for $320/share, you’ll owe tax only on the $20 of appreciation since you inherited it.

This same rule applies to mutual funds. It can provide a significant tax advantage, but it also raises an important question: do you hold on to the inherited investment or make a different decision that better fits your financial plan?

Emotions matter, too. As Clint noted, “sometimes they have an emotional attachment to some of those investments.” Keeping a sentimental stock can be fine—just make sure it still fits your retirement plan.

3. Retirement Accounts (IRAs, 401(k)s)

This is where inheritance rules can get more complex.

For non-spouse beneficiaries, most inherited retirement accounts (traditional IRAs, 401(k)s, or Roth IRAs) must be fully distributed within 10 years of the original owner’s death. That means:

- Traditional IRA/401(k): Withdrawals are taxable as ordinary income, and you have to make sure the account is emptied by the end of that 10-year window.

- Roth IRA: The 10-year rule still applies, but withdrawals are generally tax-free. You can leave the money invested for up to 10 years, then take it all at once—or spread withdrawals across those years.

For spouse beneficiaries, the rules are more flexible. A surviving spouse can:

- Roll the inherited account into their own IRA or 401(k), treating it as if it were theirs.

- Or open an inherited IRA in the deceased spouse’s name, which allows different distribution options.

So, What’s the Right Move?

It depends on a few things—like your age, income needs, and whether RMDs were already in progress. Every situation is different, and there isn’t one option that works for everyone. In summary, inherited retirement accounts can come with important tax considerations. Planning around timing, taxes, and your personal situation can help you make informed decisions.

4. Real Estate

Real estate also gets a step-up in basis to Fair Market Value (FMV) on the date of death, but your sell/hold choice drives the tax result.

Scenario: Patty inherits Grandpa Joe’s house

- Grandpa bought it for $100,000 on March 15th, 1980.

- Date of death: August 1st, 2024.

- FMV at death: $500,000 (that becomes Patty’s basis).

If Patty sells about a year later:

Loren walked through a quick sale: value rises to $510,000; after $20,000 in selling costs, there’s effectively no taxable gain.

If Patty waits 6 years and then sells:

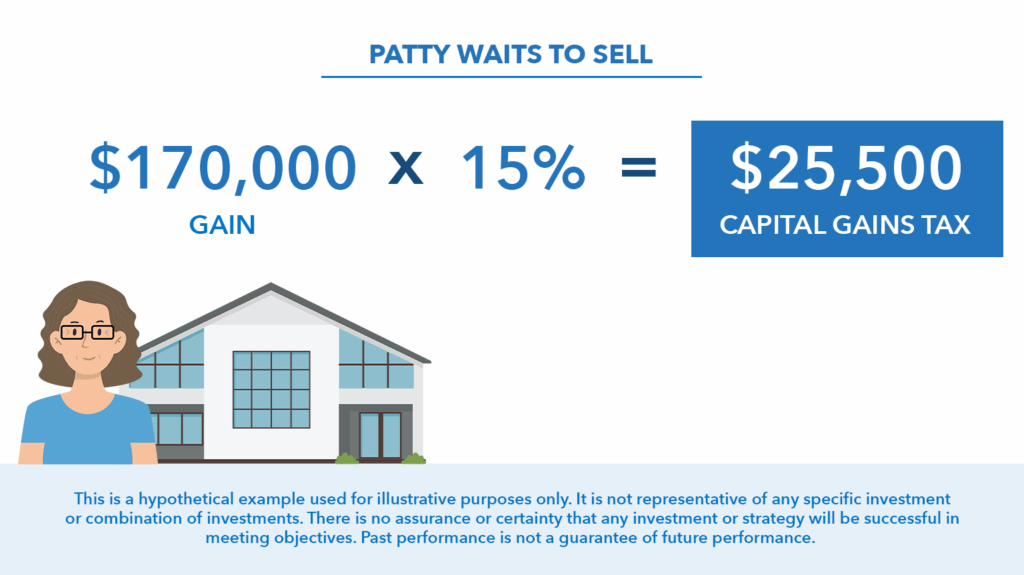

Clint modeled a bigger jump: FMV grows from $500,000 to $700,000. After deducting typical closing costs and repairs, he showed $170,000 of capital gain taxed at 15% = $25,500.

Before jumping straight to selling, though, it’s worth asking whether you even want to let go of the property. What if it’s a family lake house that holds sentimental value and you’re set to inherit it?

Loren said to consider converting it to your primary residence first. If you live there 2 out of the last 5 years before selling, current rules can exclude up to $250,000 of gain if single or $500,000 if married filing jointly.

5. Life Insurance and Annuities

Life insurance is usually the most straightforward asset to inherit. If it’s paid out in a lump sum, beneficiaries typically receive the proceeds income-tax free. This makes life insurance an efficient way to transfer wealth, since the full benefit goes directly to the people or organizations named on the policy.

Annuities, on the other hand, can be more complicated. They’re insurance contracts that may include tax-deferred growth, guaranteed payouts, or other unique features. When inherited, the rules around distribution depend on the type of annuity, how it was structured, and whether the beneficiary is a spouse or non-spouse. In some cases, taxes may apply to the gains inside the contract, and timelines for withdrawals can vary.

Because annuities come with different options and tax implications, it’s important to carefully review the contract and understand how the inheritance fits into your broader retirement planning strategy.

Align Your Legacy with Purpose

If you’re thinking about how your legacy will be passed on, it’s important to match the type of account with the right beneficiary. Loren shared how a thoughtful adjustment—like directing Roth assets to loved ones and traditional IRA accounts to charitable organizations—can help manage or potentially reduce tax impacts. Small updates to titles or beneficiaries may lead to more meaningful outcomes for the people and causes you care about most.

What to do next (and what not to do)

- Take inventory. List each asset, where it’s held, and how it’s titled.

- Match asset → rule set. Cash vs. taxable accounts vs. retirement accounts vs. real estate vs. insurance/annuities.

- Map deadlines. Some plans impose transfer windows (Clint’s 90-day example), and non-spouse IRA heirs face a 10-year clock.

- Document costs. For real estate, track selling costs and capital improvements.

- Let emotions inform—but not dictate. It’s okay to keep a sentimental stock or property if it still supports your goals.

Inheriting money is both an emotional and financial turning point. The most important step is to pause before acting. A thoughtful approach can help turn an inheritance into a meaningful part of your retirement plan.

Watch the full episode on YouTube and learn about inherited assets, key tax considerations, and strategies.